A sewer system is an essential element for any city and there have always been ways to dispose of waste generated within the home and more generally, in public. Where there are humans, there will be waste products, and to avoid diseases, bad smells and overcrowding, they need to be managed with a waste removal and management system. Sewage treatment has improved gradually throughout the ages as science has progressed in discovering the relationship between cleanliness, hygiene and good health.

Sewers

The Tudor period is well-known for bringing us many new discoveries and improvements in areas of health and human rights. Discoveries of new trade routes and the consolidation of a navy brought an influx of new things into the country, improving overall quality of life. More job opportunities were created, and there was a significant foreign population happily living and making money in England.

This naturally led to overcrowding. An increase population led to an increase in waste generated, but where was it all going? This was a time of immense pollution, so much so that even the water was undrinkable. Waste products ran in open sewers, or, more realistically, clogged the sewers that ran through the town. There was a constant smell of filth and rotting perishables that even the rich could not escape. In London, the waste was dumped straight into the Thames. It was only a matter of time before it resulted in plague, cholera, and other diseases.

Rich and Famous

Life wasn’t much more comfortable for even the rich and famous. Chamber pots were used at the time, which were then dumped outside unceremoniously, increasing the possibility of disease. At this stage, Sir John Harrington created a new invention that revolutionised how we perform one of the most basic human functions. He invented the first flushing toilet in the 1590s and installed it at his home in Kelston. The toilet had a flush valve that let the waste water out of the tank, emptying the bowl. He even had one installed for Queen Elizabeth I at Richmond Palace, though she reputedly refused to use it. Surprisingly enough, the contraption took a long time to be adopted in its country of origin.

The Thames had been used as an open sewer until the 1800s. In 1858, during one very hot summer, the entire city stank of the waste clogged up in the river. Officials started to talk about a proper sewage system to rectify the problem, and Joseph Bazalgette, the chief engineer of London’s water works, played a great role in developing the revolutionary system, which still exists today.

Bazalgette devised a connective sewage network that channelled sewage water into new low-level sewers built behind embankments of The Thames and taken to treatment centres. Gradually, sewage systems across the country improved from rudimentary to the efficient and hygienic service we now receive today. Bazalgette continued to train younger engineers throughout this time to ensure the longevity and high standards of this new and improved system.

Underground Drains

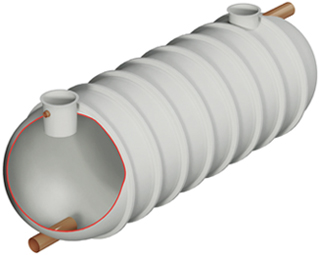

There is now a massive network of underground drains that disposes of the city’s waste in ecologically proper ways. There are septic tanks, as well as pumping stations located at strategic places through the country and the waste water is now treated, instead of being allowed to clog up the waterworks and raise a stink. Accordingly, diseases and epidemics have been reduced and eradicated.

The most important difference in the sewage system from the past is that today much of the waste generated is treated to take away its toxicity. In a country with a large per capita population, disposal of waste matter has always been a problem. Whereas earlier the waste would be thrown together in one place and left to rot and decompose on its own, that is no longer acceptable practice today. Everything that can create a stink, lead to disease or is simply not good for the environment is treated and recycled.

There are plans underway to expand the capacity of the sewage system, but until it is completed one can only estimate how much better things will be.

Go back to